Understanding Dyslexia

Creativity and Dyslexia: Strengths in Divergent Thinking

Multiple peer-reviewed studies show that many children with dyslexia display strengths in creative thinking, especially on standard tests like the Torrance Tests of Creative Thinking (TTCT). In school-age samples, dyslexic students have scored higher across TTCT components—fluency, flexibility, originality, and sometimes elaboration—with one study even finding dyslexic teens matched art-school students on overall creativity and exceeded them on flexibility. Other work shows superior performance on tasks that require unusual combinations of ideas and nonverbal creativity that is independent of IQ and literacy level. Together, these data support a strengths-based view: while reading is hard, divergent and nonverbal creative thinking can be areas of advantage for many dyslexic learners.

Dyslexic children/teens scored higher on fluency, flexibility, originality, and total creativity (TTCT studies).

Grade 4–7 learners showed higher ideational fluency across grades and higher originality in Grade 6.

Junior-high students with dyslexia outperformed peers on forming unusual idea combinations.

Dyslexic children showed higher nonverbal creativity independent of IQ and literacy level.

Context: A 2021 meta-analysis suggests the creativity advantage is clearer in adults than in children overall, so effects in youth may depend on the task and the school environment.

Dyslexia Statistics: A Crisis of Neglect

The intersection of dyslexia with suicide, Medicaid dependence, high school dropout rates, and incarceration reveals a stark pattern of systemic failure. While dyslexia is often underdiagnosed, research shows clear, high-risk pathways when educational and support systems fail.

High School Dropout Rates

- 35% of students with learning disabilities (including dyslexia) drop out of high school, compared to 6% of all students. — National Center for Learning Disabilities (2017)

- Many students remain undiagnosed, mischaracterized as lazy or disruptive, and disengage from school.

Mental Health & Suicide

- Students with dyslexia are 2–3x more likely to experience depression and anxiety.

- Those with reading difficulties are 3x more likely to consider or attempt suicide.

- Individuals with specific learning disorders (including dyslexia) are 46% more likely to have attempted suicide — American Psychological Association

- 86% of adolescents with learning disabilities considered suicide; 19% attempted it. — Margalit, 2009

- Bullying linked to reading struggles is a significant risk factor for suicidal ideation.

Incarceration & the Prison Pipeline

- 30–50% of incarcerated individuals have dyslexia or a related learning disability. — Prison Reform Trust, 2016; U.K. Ministry of Justice

- 85% of juveniles in the justice system are functionally illiterate — often due to undiagnosed dyslexia.

- Students with disabilities are twice as likely to be suspended, expelled, or arrested.

Medicaid & Economic Hardship

- Individuals with learning disabilities, including dyslexia, are more likely to live in poverty and depend on Medicaid. — U.S. Department of Education longitudinal studies

- Poor literacy is a strong predictor of lifelong unemployment and underemployment, often leading to dependency on social services.

Visual Statistics Bar (from infographic)

- 35% — High School Dropout

- 50% — Incarcerated Adults Dyslexic

- 85% — Youth in Justice System Illiterate

- 46% — LD Students Consider Suicide

- Individuals with learning disabilities, including dyslexia, are more likely to live in poverty and depend on Medicaid. — U.S. Department of Education longitudinal studies

Literacy is a Life-or-Death Issue

Early intervention in dyslexia saves futures — and lives.

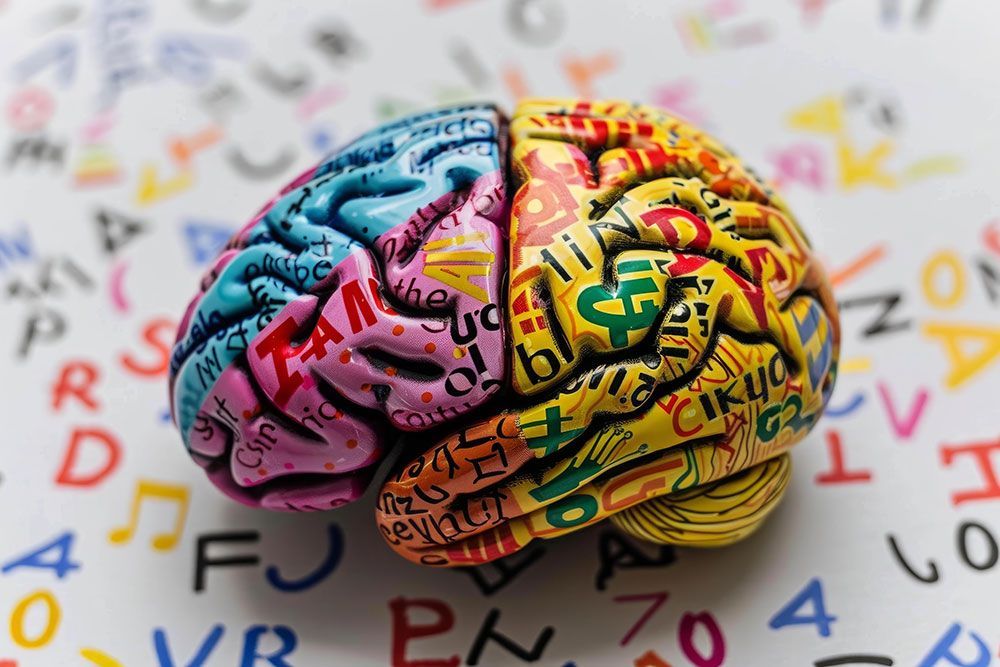

What the Neuroscience Says About Dyslexia & the Brain

1. Left Hemisphere Underactivation in Dyslexia

Research consistently shows that individuals with dyslexia have reduced activation in the left-hemisphere regions of the brain that normally support decoding and fluent reading. These regions include the occipito-temporal (OT) and temporo-parietal (TP) areas. Example: Richlan et al. (2012) meta-analysis found consistent underactivation in left TP and OT regions in dyslexic readers compared to typical readers.

2. Compensatory Right Hemisphere Activation

Dyslexic readers often show greater reliance on the right hemisphere or more bilateral brain patterns during reading tasks. These activations may serve as compensatory pathways when left-brain systems are underactive. Example: 'Reading the Wrong Way with the Right Hemisphere' showed that adults with dyslexia activated the right inferior occipital gyrus more strongly than controls during pseudoword reading tasks.

3. Neural Differences Exist Before Reading Instruction

Brain imaging shows that differences in the reading network can appear before children even learn to read, particularly in children at familial risk for dyslexia. This means dyslexia is not simply a 'failure to learn,' but reflects underlying neural circuitry differences.

4. The Effect of Intervention on Brain Activity

Systematic, explicit remediation of phonological skills (explicit instruction) can actually rewire the brain. After structured phonological training, children with dyslexia show increased activation in left hemisphere regions such as the temporo-parietal cortex and inferior frontal gyrus—patterns closer to typical readers.

5. Dyslexia & Structured Literacy (Orton-Gillingham Approach)

A growing body of research reviews the impact of structured literacy interventions (e.g., Wilson, Orton-Gillingham, Barton). A recent review: 'Current State of the Evidence: Examining the Effects of Orton-Gillingham Reading Interventions for Students with or at risk for Word-Level Reading Disabilities.' The findings show that explicit, systematic, multisensory programs are effective for struggling readers.

6. Why Orton-Gillingham & Structured Literacy Work

These methods are: Multisensory – engage sight, sound, and touch simultaneously. Systematic & Sequential – build skills step by step. Explicit – nothing is assumed; every skill is taught clearly. These components directly activate the left-hemisphere reading network that neuroscience shows is underactive in dyslexia.

Takeaway

Neuroscience confirms that dyslexia is linked to left-brain underactivation and compensatory right-brain activity. The good news is that with structured literacy (Orton-Gillingham, Wilson, Barton, etc.), the brain can be retrained—restoring left-hemisphere activity and unlocking a child’s ability to read.

Downloads

Understanding the Revised IDA Definition of Dyslexia - A Companion Guide

Understanding Dyslexia The IDA Definition of Dyslexia

Wyoming Dyslexia's Crisis

The Spectrum of Dyslexia

What is Double Dyslexia?

Neuroscience confirms that dyslexia is linked to left-brain underactivation and compensatory right-brain activity. The good news is that with structured literacy (Orton-Gillingham, Wilson, Barton, etc.), the brain can be retrained—restoring left-hemisphere activity and unlocking a child’s ability to read.

1. What It Means

- Weakness in phonological processing (trouble connecting sounds to letters) •

- Weakness in rapid naming/processing speed (trouble quickly naming letters, numbers, or colors)

When BOTH are present, a child is considered to have “double dyslexia,” often resulting in the most severe reading difficulties.

2. Key Characteristics

- Extreme difficulty decoding words despite years of instruction

- Very slow reading rate, even when accuracy improves

- Poor spelling and written expression • Struggles with subjects that require reading (math word problems, directions, note-taking)

- Emotional toll: higher risk of anxiety, depression, school refusal

- Lifelong impact: may never test at grade-level, even after strong interventions

3. Why It Matters

Students with double dyslexia need the MOST intensive support:

- Daily 1:1 or very small group evidence-based intervention (Wilson, Barton, Orton-Gillingham) • Extended School Year (ESY) to prevent regression

- Progress measured by a body of evidence (lesson mastery, fluency, observed skills), not just standardized tests

4. The Most Profound Form

- Dual deficits = slowest progress without proper instruction

- Requires years of structured literacy instruction

- Continued support into middle and high school

- Reading may improve, but fluency and writing remain challenges

With the right instruction, children with double dyslexia CAN learn to read, but they need more time, more intensity, and strong IEP protections.

Understanding Mild Dyslexia: Compensated with Consistent Supports

Mild dyslexia affects many children. These students may not struggle as severely as others with reading, but they still need help to succeed. Without the right support, even mild dyslexia can cause frustration, self-doubt, and falling behind in school.

What Does “Compensated” Mean?

Children with mild dyslexia can often work around their reading challenges when given the right tools and strategies:

- They might rely on their strong memory, creativity, or listening skills.

- They learn to “compensate” for difficulties in decoding words by using alternative strengths.

- Compensation does not mean dyslexia goes away—it means the child finds ways to cope.

What Are “Consistent Supports”?

Supports must be ongoing, reliable, and predictable—not just occasional help. Examples include:

- Classroom Accommodations: Extra time, audiobooks, text-to-speech, teachers reading directions aloud.

- Instructional Supports: Small-group or one-on-one instruction, systematic phonics, multisensory teaching.

- At-Home Supports: Reading aloud together daily, homework help, encouragement and positive reinforcement.

Why Consistency Matters

- Inconsistent support can cause a child to slip through the cracks.

- With steady, structured help, children with mild dyslexia can thrive academically, build confidence, and discover their potential.

- Without it, even mild dyslexia can lead to unnecessary struggles in school.

Remember

“Mild dyslexia: majority of cases, often compensated with consistent supports” means your child may succeed if the right help is provided every day, in every setting—but they still need that help. Consistency is the key to building long-term success.

Dyslexia is lifelong, but with strong and reliable supports, your child’s ability to read, learn, and grow can flourish.

Understanding Dyslexia

Having dyslexia doesn't mean people aren't smart. It means they have trouble with reading and other skills that involve language. Here are common signs to look for at different ages.

Preschool

- Mispronouncing words, like saying "beddy tear" instead of "teddy bear"

- Saying "thing" and "stuff" instead of naming common objects

- Trouble learning nursery rhymes or singing the alphabet

- Telling stories that are hard to follow

- Difficulty following directions with multiple steps

Grades K–2

- Trouble learning letter names and remembering the sounds they make

- Confusing letters that look similar (like b and d) or sound similar (like f and v)

- Struggling to read familiar words (like cat), especially if there aren't pictures

- Substituting words when reading aloud, like "house" when the story says "home"

- Trouble separating the sounds in words and blending sounds to make words

- Struggling to remember how words are spelled

Grades 3–5

- Confusing or skipping small words like "for" and "of" when reading aloud

- Trouble sounding out new words and recognizing common ones

- Struggling to explain what happened in a story or answer questions about it

- Frequently making the same kinds of mistakes, like reversing letters

- Spelling the same word correctly and incorrectly in the same exercise

- Avoiding reading whenever possible or getting frustrated or upset when reading

Tweens, Teens, and Adults

- Reading slowly or skipping small words or parts of words when reading aloud

- Often searching for words or using substitutes like "gate" instead of "fence"

- Trouble "getting" jokes or understanding idioms, puns, and abbreviations

- Taking a very long time to complete reading assignments

- Having an easier time answering questions about text that's read aloud

Remember: Early identification and support can make a significant difference. If you notice these signs, consider consulting with educational professionals or specialists.

The Dyslexia Iceberg

What We See vs. What's Hidden Beneath

Like an iceberg, dyslexia shows only a small portion of its impact above the surface. The visible academic struggles are supported by a much larger foundation of emotional and psychological effects that often go unrecognized.

Visible Signs

- Staring into Space

- Difficulty Talking

- Socializing Challenges

- Work Avoidance

- Frequent Nurse Visits

- Visits Well with Adults

- Poor Comprehension

- Poor Fluency

- Word Recall Issues

Hidden Beneath the Surface

- Depression

- Anxiety

- Tantrums/Meltdowns

- Suicidal Ideation

- Calling Themselves "Stupid"

- Feeling Hopeless

- Low Self-Esteem

- Suicide Risk

- Family Impact

- High Pain Tolerance

- Stimulation Seeking

Critical Understanding: The visible academic struggles are just the tip of the iceberg. The hidden emotional and psychological impacts require immediate attention and support. If you notice signs of depression, anxiety, or any mention of self-harm, seek professional help immediately.